In 1942, Roger Damoiseau senior – a former engineering graduate of the Institut Electrotechnique de Grenoble and the Institut Catholique d’Arts et Métiers – decided to purchase the Bellevue estate, which was derelict up to that point, but this came at the price of a heavy debt. The company resumed its business of producing sugar, making sweets and jams. Subsequently, rum would soon become the main focus of production.

History of Damoiseau

Our roots and those of our sugar cane

In 1968, Roger Damoiseau junior took over from his father and continued to develop the family business to the point of being able to pay off the company’s debt through bulk rum sales. His sons then began to work with him, helping him to make the distillery a successful business.

It was in 1995 that Roger handed over to Hervé Damoiseau who became the chairman, his brother Jean-Luc handling production. In 1978, Jean-Luc became a master distiller, and since then, their sister Sandrine Damoiseau has been promoting the brand through events.

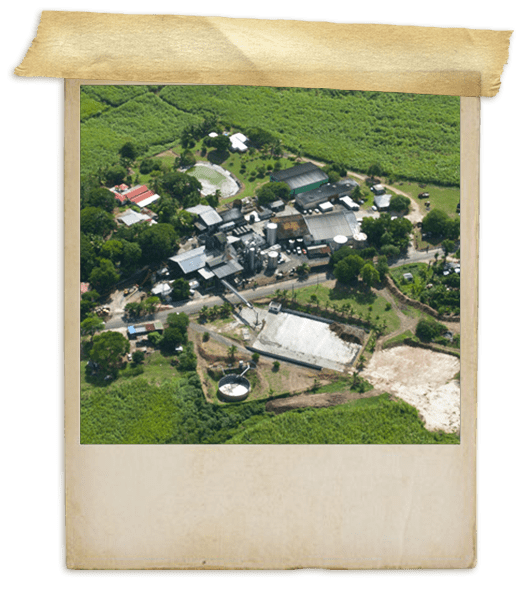

The sunny microclimate and naturally lime-rich soil – which promote sugar cane growth – are the Damoiseau distillery’s strengths. These advantages mean fully mature crops for the only distillery in Grande-Terre.

Our history

Interview with Jean-Luc Damoiseau

Master distiller & managing director of Rhums Damoiseau

What changes in equipment at the distillery characterised the stages of Rhums Damoiseau?

When I started out, the cane yard had a dirt floor, and we would just weigh the carts. We would get through around 50 tonnes per day when the weather was fine. The cane conveyor was underground, to be tipped manually. There were two mills powered by a steam engine, Burton juice pumps (also steam-driven), very old-world… but that generation worked hard and did not lack courage.

‘‘ The fermentation tanks – bought second-hand by my father, who everyone called ‘‘Ti-Roger’’ (little Roger) at the time – were made from black sheet metal, and we would spend a lot of time welding the plates together to make them watertight. We still had to monitor them 24/7 for leaks though... Us during the day and the watchman at night – we managed to minimise losses with little bits of wood and sandbags! ’’

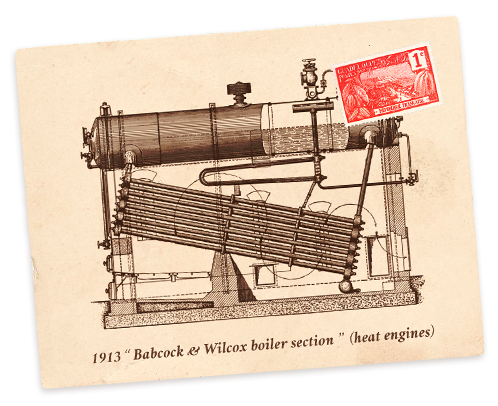

The Babcock boiler was installed by Roger senior (aka ‘Papa Roger’) who had bought it second-hand from EDF (before Spedeg) and dismantled it at the Baie-Mahault power plant. You needed muscles back then, because as the moisture content of bagasse is not high enough, we had to burn over two tonnes of wood a day to have enough steam for the mills and distillation.

Bottling was done manually. Faber would fill and cap, and Fifille would stick the labels on. We would average 100 to 110 12-bottle racks per day. The distillery had an 18 kVA Lister generator, as we weren’t connected to the grid… Now it runs on over 900 kVA!

‘‘ As soon as we had electricity, the first improvement was a cane shredder powered by an electric motor and a second-hand semi-automatic Girondine bottle filler. You had to be a good footballer to stop the bottles that would come off the rails... but we were able to sell more! ’’

We salvaged the washer from Héritiers Roger Damoiseau (the distribution company my grandfather had established in Pointe-à-Pitre), because they had just acquired new machines, to triple sales. Grands Rhums Charles Simonnet dominated the market… we accounted for around 6 to 7 % of the local market.

Micro distilleries closed one after the other. In Morne-à-l’Eau, there were two – one in Sainte-Anne, one in Bragelone – and others. Factories were having a clear-out too, as reforms at the time called for a maximum of one or two units. So Darboussier, Sainte Marthe, Blanchet & Bonne Mère all closed.

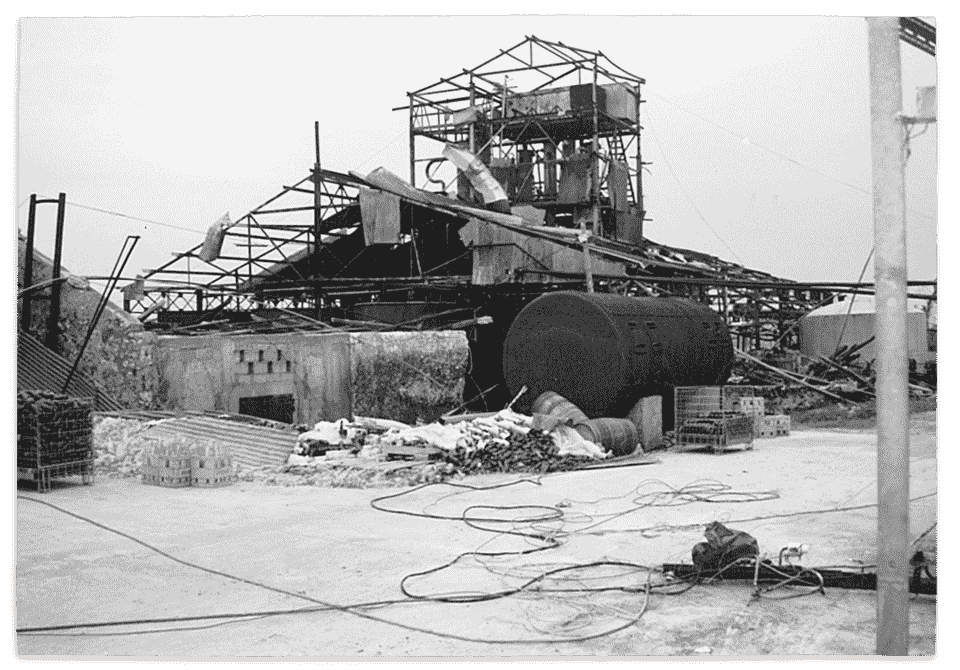

‘‘ Cyclone Hugo in 1989 brought us to a halt... we realised that the production facility had fallen behind. ’’

The priority was to rebuild. Fortunately, my father was there to help me (he even picked up the bottles that hadn’t broken in the aftermath of the disaster). I handled the distillery and he the warehouses and storage. The bottling shed had lost its roofing; we salvaged the twisted metal all around us to repair it, then got it operational again. We also salvaged EDF electrical cables that were scattered along the roads (due to the cyclone), so we could restore power to the houses, the distillery and the only warehouse we had left.

In 1992, we installed a new boiler and mill (bought second-hand from Longueteau). I sent this mill to Brazil for them to convert it into a four-roller, then I installed a second shredder, to make sure we had a bagasse moisture content below 50 %.

‘‘ Anecdote: I had sworn that never again would I embark on the installation of a mill... I have installed three others since then! ’’

‘‘ Around 1994, the local quota was lifted, so we could sell as much as we wanted. I can’t explain why, but nothing could stop us any more... ’’

We set up our first storage and ageing facility, while gradually modernising the distillery. In it, we installed a Stone bottle filler (1,800 bt/hr), and later with Régis (his brother who died in 2004), we expanded the warehouse and put in a new 4,500-bt/hr bottle filler.

‘‘ The distillery is now one of the most efficient industrial facilities in the Antilles. ’’

We have two (hammer-anvil) shredders and four fully automated four-roller mills with Donnelly chutes. We easily achieve a throughput of 30 t/hr with extraordinary sugar extraction. We have less than 2 % sugar remaining and a moisture content below 48 %.

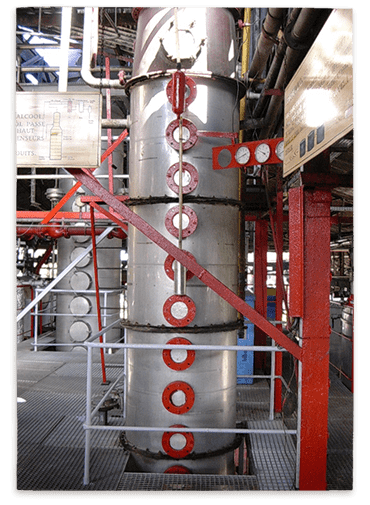

The columns have also changed. The first one we bought second-hand from Bonne Mère then converted the concentration part (created at the time for molasses). When we put in the second one, we took the opportunity to install evaporation chambers downstream to filter out the oils present in the steam.

Three years ago, I installed a column capable of distilling more wash than the other two. This column has a degassing column at the top and a thermo-syphon system to save steam, as we need steam for vinasse processing.

‘‘ The manufacturing side has grown thanks to everyone who helped me:

without the knowledge and devotion of Jacky (former employee of the distillery),

I would never have made it this far. ’’

What are the names of the different columns?

The first one: down below, Speichim and up top, Roger.

The second one Iméca, with the plans by engineer Pierre Olivier Cogat.

And the last one Honoré, again with the plans by Pierre Olivier Cogat.

What do you consider to be the biggest technical development in terms of production?

It’s a combination – technology knows no bounds;

I realise that I’m rather outdated

and more importantly don’t share the same motivations.

What things would you like to implement

at the distillery to improve its system?

What remains to be done is a question of automation.

All sectors are automated, but if we put our heads together, we could do better.

A more efficient bottle filler and a quality ageing cellar,

because we have fallen behind in this area,

like the majority of our fellow Guadeloupeans.

I hope to leave my family with a facility they will all be proud to be a part of, because there is still a long way to go…

Lastly, in your opinion, what are the highlights in Damoiseau’s history ?

Roger Damoiseau senior bought the distillery (in Rue Achille René Boisneuf) without a penny to his name, and his notary public friend Mr Thionville helped him. He set up the bare essentials – a boiler, the mills and storage.

The mills came from Grosse-Montagne; there was a shredder and three mills.

He sold a mill to pay for the installation of two others… he never got the money.

Roger junior was repaying the debts from these investments his whole life.

When Hugo (1989 cyclone) hit, we had just finished paying back the Ines loan.

He dedicated his life to work and his children.

‘‘ All I ever did was move forward, with my time and my thirst for success; Régis and I dreamed of succeeding...

At night, we would lie on the lawn (no electricity or air con), and we would look at the sky; we would talk about everything we wanted to do and have... and more!’ ’’